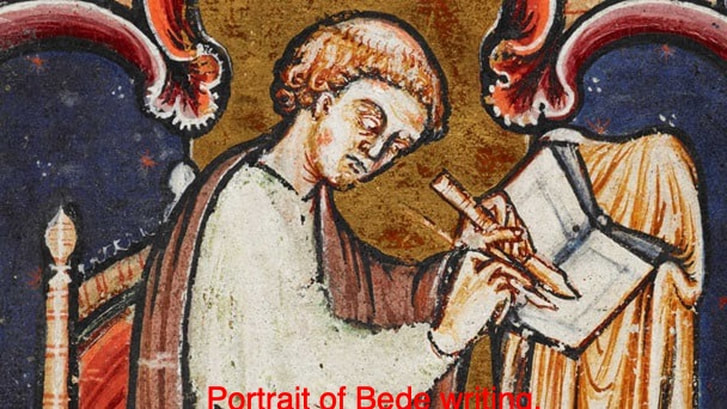

ANGLO-SAXON MONTHSWe are used to the Roman month names that go from January to December. But long before these names were adopted into English, Germanic calendar that had been brought to England from mainland Europe by Anglo-Saxon settlers was used to divide the year into 12 (or sometimes 13) lunar months. The earliest and most detailed account we have of this pre-Christian calendar comes from Bede, an 8th century monk and scholar based in Jarrow in northeast England, who outlined the old Anglo-Saxon months of the year in his work De temporum ratione, or “The Reckoning of Time,” in AD 725. January, Bede explained, corresponds to an Anglo-Saxon month known as Æftera Geola, or “After Yule”—the month, quite literally, after Christmas. February was Sōlmōnath, a name that apparently derived from an Old English word for wet sand or mud, sōl; according to Bede, it meant “the month of cakes,” when ritual offerings of savory cakes and loaves of bread would be made to ensure a good year’s harvest. It’s plausible that the name Sōlmōnath might have referred to the cakes’ sandy, gritty texture. March was Hrēðmonath to the Anglo-Saxons, and was named in honor of a little-known pagan fertility goddess named Hreða, or Rheda. Her name eventually became Lide in some southern dialects of English, and the name Lide or Lide-month was still being used locally in parts of southwest England until as recently as the 19th century. April corresponds to the Anglo-Saxon Eostremonath, which took its name from another mysterious pagan deity named Eostre. She is thought to have been a goddess of the dawn who was honoured with a festival around the time of the spring equinox, which, according to some accounts, eventually changed into our festival of Easter. Oddly, no account of Eostre is recorded anywhere else outside of Bede’s writings—but it seems unlikely that Bede would have invented a fictitious pagan festival in order to account for a Christian one. May was Thrimilce, or “the month of three milkings,” when livestock were often so well fed on fresh spring grass that they could be milked three times a day. June and July were together known as Liða, an Old English word meaning “mild” or “gentle,” which referred to the period of warm, seasonable weather either side of Midsummer. To differentiate between the two, June was sometimes known as Ærraliða, or “before-mild,” and July was Æfteraliða, or “after-mild;” in some years a “leap month” was added to the calendar at the height of the summer, which was Thriliða, or the “third-mild.” August was Weodmonath or the “plant month.” After that came September, or Hāligmonath, meaning “holy month,” when celebrations and religious festivals would be held to celebrate a successful summer’s crop. October was Winterfylleth, or the “winter full moon,” because, as Bede explained, winter was said to begin on the first full moon in October. November was Blōtmonath, or “the month of blood sacrifices.” The purpose of this late autumnal sacrifice might have been propitious, but it’s likely that any older or infirm livestock that seemed unlikely to see out bad weather ahead would be killed both as a stockpile of food, and as an offering for a safe and mild winter. And December, finally, was Ærra Geola or the month “before Yule,” after which Æftera Geola would come round again. Use of the Germanic calendar dwindled as Christianity—which brought with it the Roman Julian Calendar—was introduced more widely across England in the Early Middle Ages. It quickly became the standard, so that by the time that Bede was writing he could dismiss the “heathen” Germanic calendar as the product of an “olden time.” INSIGHT INTO INSPIRATIONThe inspiration behind writing a Saint Cuthbert trilogy came from recognition of the enduring memory of the golden age of Northumbrian monasticism. There are statues and re-enactments and even reproduction villages in the north-east of England in the twenty-first century. We are talking about a legacy of over a thousand years. The saints concerned are especially St Aidan, St Cuthbert and St Bede. I would like to draw your attention (please click below for link) to this remarkable initiative: /Jarrow Hall Returning to my inspiration, I began thinking not just of the impact of Saint Cuthbert in life, but also the subsequent effect his life had on successive generations of Anglo-Saxons and indeed beyond into the Norman period. Therefore, inspired by the incredible journey undertaken on foot by devoted monks who tramped around the north of England carrying the saint's remains on their shoulders in a heavy coffin for a total of 600 miles - imagine that! I wrote my second of the trilogy entitled The Horse-thegn. I like to include aspects of daily life in my novels and here, I deal with the importance of horses to the Anglo-Saxons, whereas in the first of the series Heaven in a Wild Flower, featuring Cuthbert in life, I write about a leather-worker and a scribe. Talking about scribes, I bless the social media for allowing me to get to know a fabulous modern-day Scottish scribe and re-enactor, Dawn Burgoyne. This incredibly patient lady is a brilliant interpreter of medieval calligraphy and I have the good fortune to have her contributing exquisite frontispieces to my novels. Currently, she is preparing me an illuminated extract from Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Since these things take time and enormous patience, I contacted Dawn before I even have a title for Book 3 and am only on Chapter eleven. Students of Anglo-Saxon history will understand the incredible importance to our knowledge of the times the Venerable Bede contributes even allowing for monastic bias. But he, also, like Cuthbert, had an enduring effect on subsequent generations. His Historia inspired an Anglo-Saxon monk, Alwyn, to leave his abbey in Evesham and traipse up to Jarrow to restore the former glory of the devastated monastery. He attempted this for Melrose and Monkwearmouth, too, and indirectly, Whitby. So, as ever, attempting to capture daily life, I write about the mason entrusted to recreate the destroyed churches and cloisters. It is fascinating researching the medieval master mason's methods and tools. So, what better frontispiece for this untitled book than an extract from Bede faithfully reprroduced by the patient and talented Dawn? Here's a promise for you. As soon as Dawn consigns it to me, I'll publish it on this Blog and when my brain snaps into action and I have a title, I'll let you know. Till then, it's back to the lime kiln and the straight-edge! Below: Portrait of Bede writing, from a 12th-century copy of his Life of St Cuthbert (British Library, Yates Thompson MS 26, f. 2r)T

Get a free eBook!Join my newsletter & receive a free digital copy of Heaven in a Wildflower, book 1 of my St. Cuthbert Trilogy, as well as monthly news, insights, historical facts, & exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox! Thank you!You have successfully joined my mailing list!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

To buy your copy of Rhodri's Furies click the link below:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Rhodris-Furies-Ninth-century-Resistance-incursions-ebook/dp/B0BPX9C2D3/ |