|

My friendship with Paolo Valente dates from 1986 when he, who is now bilingual, was learning English and I was teaching the language. He was one of my best students, so it was natural to socialise with him: it helped my Italian and his English. Now, Paolo is capable of reading my novels. I’m honoured that he enjoys them. I have suggested to my publishers, who have enthusiastically accepted the idea, that Paolo’s ‘Viking music’ be used in my Sceapig trilogy audiobooks. Book 1 is The Runes of Victory; Book 2 is Sea Wolves and Book 3 is as yet untitled as I’m writing it. In the near future all three will be released in audiobook format. But enough about me. Let’s hear what Paolo has to say: The passion for the Vikings history goes back to my school years. I’ve always been fascinated by their strong, courageous warriors. Recently, I started following the History Channel series The Vikings and I really enjoyed Ragnar’s family saga but what really caught my attention was the music of the soundtrack. Recently, I have also read several of John Broughton’s historical novels, many of which cover the eighth- to tenth-century Viking incursions. Most recently, his trilogy set on the Isle of Sheppey captivated my attention: I couldn’t put down The Runes of Victory and I’m looking forward to the sequels. I thought that I would like to create something similar with my own interpretation. Of course, this cannot be real Viking music as I don’t have their original instruments, but I wanted to create something as close as possible to the original feeling. Thanks to modern technology, I managed to reproduce what my imagination of moments of Viking life suggested to me: battles, seafaring, conquest of new lands or whatever. Whether I succeeded in transmitting this message through my music, I’m not sure, but certainly it gave me that feeling of when you close your eyes you plunge into the action. I hope it carries over to the listeners. As for the technology I use, first, a midi controller with Ableton live for the rhythm parts and then a mini-synthesiser for the solos. This represents a progression in my musical career, which began as a Blues musician playing guitar and harmonica to move on to more generic performances including singer-songwriter. I have performed solo or in bands, my first group was called The Midnight Ramblers. Among other things, I organised several blues festivals in my home town, which involved renowned international musicians and achieved national coverage in the Press. Listen to Paolo's Viking music below:

0 Comments

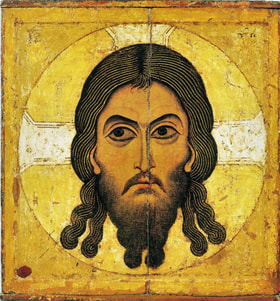

The Importance of the Senses in Writing Since the human being has five senses (if not six), to describe the feelings, sentiments and sensations of the characters is obligatory for the author. Showing not telling them is the art. If the writer can enter into the reactions of his characters it is job done. How we react to the stimuli of art and music would be a good example. I try to capture my feelings and transpose them to my characters. For the historical novelist this becomes more difficult since he has to contend with the changes wrought by time. I would like to illustrate what I mean by drawing from my first novel The Purple Thread. In this novel, the main character, Begiloc, a British warrior tramps around the Europe of his day escorting Christian missionaries. On his journey he carries a hearpe with him. This instrument was more like a lyre than a harp and given that he crafted it himself, would have been rudimentary. I have borrowed an example from You Tube and all credit should go to Mr Peter Horn, a re-enactor. Begiloc would have sounded like the video above. Later in the novel, Begiloc’s best friend, Meryn, now blinded by his enemies, finds salvation in music and becomes the Chant Master in a monastery just when the Gregorian chanting is changing from Galician to Roman. What does that mean? Let’s ask Meryn; here is an extract from the novel: “The difference between the Gallican and the Roman chant is the former is more florid ...” ‘Has he heard me? Is he mad?’ “... like this – ah – aah –aah – on each syllable in an upward pitch where— ” “Damn the Gallican chant! Did you hear me? I said I fulfilled my oath.” The blind man sighed and stood. Crossing the room, he groped for a small box, removing Talwyn’s brooch and holding it out to his friend. “Take it!” he said, voice sorrowful, “this is a constant reminder of my sinful past. Indeed, of the heaviest sin blackening my soul.” His tone changed to one of reproval, “Had you come but once to find me, I should have released you from your vow.” ‘What! He has gone mad! Why? Milo stole your sight, bedded other men’s wives, virgins! Had men castrated, plundered the Church ...’ Begiloc ground his teeth. Now let’s listen to a fine example of the Galician Chant interpreted nowadays (scroll down to listen). It is not just music that the novelist can exploit. What about art? In our descriptions the characters can find themselves in the presence of great art. How do they feel? Let’s turn again to Begiloc when he finds himself, to his amazement, summoned to Rome to the greatest cathedral in the world at the time: St John in Lateran. How does he feel? To Begiloc’s left hung a painting, a picture of Christ on wood. Convinced the brown eyes of the icon were studying him, he could not detach his gaze but the work also enthralled his companions. In an awed voice, Boniface said, “The Acheiropoieton. The word means ‘made without hands’.” “How can it be?” Begiloc asked. “They say St Luke painted it with the help of an angel.” “Could be. I don’t like the way it stares at me. It knows I’m a sinner.” Averting his gaze, he refused to look in that direction. For the warrior, an eternity passed before the summons into the presence of Gregory III. Willibald stood smiling as they entered. The Pontifex rose from his bowl-shaped throne and they knelt before him. The heart of Begiloc pounded and he wished himself anywhere but here. Isn’t the Acheiropoieton a little disturbing? Just look at those eyes! So, to conclude, I believe there are opportunities everywhere to describe the senses. I have chosen two, but what about the smell of freshly-baked bread? The scent of cherry blossom? The caress of a soft hand on the cheek? The opportunities are endless to take the reader into the sensations undergone by our characters. We authors have only to set them up. ANGLO-SAXON MONTHSWe are used to the Roman month names that go from January to December. But long before these names were adopted into English, Germanic calendar that had been brought to England from mainland Europe by Anglo-Saxon settlers was used to divide the year into 12 (or sometimes 13) lunar months. The earliest and most detailed account we have of this pre-Christian calendar comes from Bede, an 8th century monk and scholar based in Jarrow in northeast England, who outlined the old Anglo-Saxon months of the year in his work De temporum ratione, or “The Reckoning of Time,” in AD 725. January, Bede explained, corresponds to an Anglo-Saxon month known as Æftera Geola, or “After Yule”—the month, quite literally, after Christmas. February was Sōlmōnath, a name that apparently derived from an Old English word for wet sand or mud, sōl; according to Bede, it meant “the month of cakes,” when ritual offerings of savory cakes and loaves of bread would be made to ensure a good year’s harvest. It’s plausible that the name Sōlmōnath might have referred to the cakes’ sandy, gritty texture. March was Hrēðmonath to the Anglo-Saxons, and was named in honor of a little-known pagan fertility goddess named Hreða, or Rheda. Her name eventually became Lide in some southern dialects of English, and the name Lide or Lide-month was still being used locally in parts of southwest England until as recently as the 19th century. April corresponds to the Anglo-Saxon Eostremonath, which took its name from another mysterious pagan deity named Eostre. She is thought to have been a goddess of the dawn who was honoured with a festival around the time of the spring equinox, which, according to some accounts, eventually changed into our festival of Easter. Oddly, no account of Eostre is recorded anywhere else outside of Bede’s writings—but it seems unlikely that Bede would have invented a fictitious pagan festival in order to account for a Christian one. May was Thrimilce, or “the month of three milkings,” when livestock were often so well fed on fresh spring grass that they could be milked three times a day. June and July were together known as Liða, an Old English word meaning “mild” or “gentle,” which referred to the period of warm, seasonable weather either side of Midsummer. To differentiate between the two, June was sometimes known as Ærraliða, or “before-mild,” and July was Æfteraliða, or “after-mild;” in some years a “leap month” was added to the calendar at the height of the summer, which was Thriliða, or the “third-mild.” August was Weodmonath or the “plant month.” After that came September, or Hāligmonath, meaning “holy month,” when celebrations and religious festivals would be held to celebrate a successful summer’s crop. October was Winterfylleth, or the “winter full moon,” because, as Bede explained, winter was said to begin on the first full moon in October. November was Blōtmonath, or “the month of blood sacrifices.” The purpose of this late autumnal sacrifice might have been propitious, but it’s likely that any older or infirm livestock that seemed unlikely to see out bad weather ahead would be killed both as a stockpile of food, and as an offering for a safe and mild winter. And December, finally, was Ærra Geola or the month “before Yule,” after which Æftera Geola would come round again. Use of the Germanic calendar dwindled as Christianity—which brought with it the Roman Julian Calendar—was introduced more widely across England in the Early Middle Ages. It quickly became the standard, so that by the time that Bede was writing he could dismiss the “heathen” Germanic calendar as the product of an “olden time.” INSIGHT INTO INSPIRATIONThe inspiration behind writing a Saint Cuthbert trilogy came from recognition of the enduring memory of the golden age of Northumbrian monasticism. There are statues and re-enactments and even reproduction villages in the north-east of England in the twenty-first century. We are talking about a legacy of over a thousand years. The saints concerned are especially St Aidan, St Cuthbert and St Bede. I would like to draw your attention (please click below for link) to this remarkable initiative: /Jarrow Hall Returning to my inspiration, I began thinking not just of the impact of Saint Cuthbert in life, but also the subsequent effect his life had on successive generations of Anglo-Saxons and indeed beyond into the Norman period. Therefore, inspired by the incredible journey undertaken on foot by devoted monks who tramped around the north of England carrying the saint's remains on their shoulders in a heavy coffin for a total of 600 miles - imagine that! I wrote my second of the trilogy entitled The Horse-thegn. I like to include aspects of daily life in my novels and here, I deal with the importance of horses to the Anglo-Saxons, whereas in the first of the series Heaven in a Wild Flower, featuring Cuthbert in life, I write about a leather-worker and a scribe. Talking about scribes, I bless the social media for allowing me to get to know a fabulous modern-day Scottish scribe and re-enactor, Dawn Burgoyne. This incredibly patient lady is a brilliant interpreter of medieval calligraphy and I have the good fortune to have her contributing exquisite frontispieces to my novels. Currently, she is preparing me an illuminated extract from Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Since these things take time and enormous patience, I contacted Dawn before I even have a title for Book 3 and am only on Chapter eleven. Students of Anglo-Saxon history will understand the incredible importance to our knowledge of the times the Venerable Bede contributes even allowing for monastic bias. But he, also, like Cuthbert, had an enduring effect on subsequent generations. His Historia inspired an Anglo-Saxon monk, Alwyn, to leave his abbey in Evesham and traipse up to Jarrow to restore the former glory of the devastated monastery. He attempted this for Melrose and Monkwearmouth, too, and indirectly, Whitby. So, as ever, attempting to capture daily life, I write about the mason entrusted to recreate the destroyed churches and cloisters. It is fascinating researching the medieval master mason's methods and tools. So, what better frontispiece for this untitled book than an extract from Bede faithfully reprroduced by the patient and talented Dawn? Here's a promise for you. As soon as Dawn consigns it to me, I'll publish it on this Blog and when my brain snaps into action and I have a title, I'll let you know. Till then, it's back to the lime kiln and the straight-edge! Below: Portrait of Bede writing, from a 12th-century copy of his Life of St Cuthbert (British Library, Yates Thompson MS 26, f. 2r)T

WHY THE OLD SAXON? My father used to tell a story, probably apocryphal, about the Second World War when he served as a stretcher bearer in the RAMC. A friendly American soldier approached him, “Hi buddy! Where are you from?” “England.” “New England?” Father, touched to the quick: “No, pal, Little Old England!” So, what has this to do with my latest novel – John the Old Saxon? Well, ‘old’ does not refer to John’s age although for the ninth/tenth century he lived to a ripe old age. No, it refers to Old Saxony, which term King Alfred’s contemporaries used to refer to the German Saxony to distinguish it from ‘New Saxony’, that is, Wessex. Middle-aged when he arrived in England, John, therefore, was an Old Saxon. In the dark past, some figures like Alfred shine brightly, thanks also to available documentation such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, for which that king was responsible. Yet, he was surrounded by figures who move around him like shades seen through the almost impenetrable shroud of Time. One of these was the undoubtedly influential scholarly figure of John the Old Saxon. Such is his obscurity (or self-effacement?) that even his identity and actual burial site is subject to discussion among historians. As a historical novelist I have enjoyed the privilege of using my imagination to fill some gaps in our knowledge. Hopefully, there is a significant amount of truth in my efforts. I hope to bring to life John the Old Saxon for my readers. REFLECTIONS ON ORIGINALITY AND AUTHENTICITYTowards the end of my latest novel, my beta reader who follows me chapter by chapter made a comment that set me thinking. He said, that episode reminds me of the Murder in the Cathedral. Yes, except that the incident concerned happened some 275 years earlier! Which brings me to my point. Upon listening to the audiobook of my Perfecta Saxonia, an American troll gave it a 1-star review – (all the others are 5-star) claiming that it was plagiaristic- a poor copy of Bernard Cornwell. Much as I like and respect Bernard’s books, I would never knowingly copy him and I’m very careful about such things. All my work is original unless I quote. What the American confused was a person writing about the same historical events: the poor chap couldn’t distinguish the difference of plot and style evidently. But I wish to make the point that creating an original Dark Ages novel that has not been well dealt with by someone else is tricky. When I finished my St Cuthbert Trilogy, I had half a mind to have a go at writing about the fascinating Saint Dunstan – that proved a non-starter because it had just been done extremely well and was published last year. No problem, I’ve found another avenue for a new trilogy, but the fact is that so many Dark Age personages have been covered. Here I could write a long list of characters I’ve wanted to write about but rejected on the grounds that they’ve been well covered by others – first among these the Lady of the Mercians – Aethelflaed – a fascinating woman. Maybe one of the problems of originality when writing about the Anglo-Saxon period is the lack of documentary material. We have The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Bede to guide us but that’s about it and even they are not necessarily without bias. The answer is to break away from great personages as much as possible: my recent work has centred on more humble characters like a leather worker, a scribe, a stone mason and so forth. They encounter the great, literally, as my scribe-scholar rubs shoulder with King Alfred in my latest novel. I was amused by a recent excellent review, where the reviewer touched on the humility of the two main characters in The Master of the Chevron because while it’s true that we know little or nothing about the first master mason of Durham Cathedral, we know a lot about Prior Thurgot, thanks also to an almost contemporary account of his life. It meant a lot to me that I had been able to introduce this exceptional monk to a modern-day reader who probably had never heard of him. I think that the fun of writing about the Anglo-Saxons is trying to travel back in time mentally to capture the life in those days as much as possible. I fear that attempts at originality can be dangerous in terms of respecting authenticity. But worrying about that helps me to be a better writer. We all have to deal with trolls apparently. I’m lucky to only have had one! SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A NOVEL?Everybody has a book in them or so the saying goes. Like every profession, being an author requires a professional approach. That means learning the trade often the hard way.

So, you wake up one morning and decide to write a novel? Unlikely. Probably it’s been a slow and steady process of realisation. Then you are faced with the question – why? Why go to all that trouble? Do you want to write to make money? Or do you wish to write as a hobby? The former is a very steep and rocky road as the competition out there is formidable. Nowadays, there are computers and word processors; whereas, at one time, people banged out stories on a typewriter on paper with no automatic spell-checker and writers in those days were generally proficient in grammar—including punctuation. Publishers and agents served as gatekeepers accumulating enormous slush piles. Today, you can self-publish almost unchecked, hence the atrocious level of English in many, not all, self-published books. There is an industry grown up around the indie writing community worth a fortune. It sells books on how to write a novel. It has grown into a many-headed giant because there are so many aspects of writing to analyse. So, who to believe? Are these experts bestselling authors themselves? You’re kidding! If they were, they’d be busy writing another blockbuster. That’s not to say they don’t offer good advice. Sure, they do. But the best advice, in my opinion was offered by the great Joseph Conrad. “Write your first 250000 words for the waste bin.” That is, learn by doing and he knew what he was talking about, yet even so, this indisputably great writer’s first approach to publishers was met by 19 rejections. So, he taught us another valuable lesson – perseverance. Sit down and write; eliminate the noise. Well then, the people who actually make a living from writing are a miniscule minority of the millions who publish every year. They are not approaching writing as a hobby and concentrate on what the market wants. The people who write as a hobby do it for several reasons, among these: a love of the genre. If you adore your genre; you may find it’s not the most popular. Except that it can be. Take my genre, historical fiction. It can’t compete with historical romance or sci-fi. Except that there are exceptions like Ken Follett or Bernard Cornwell: thank goodness. Now, I’ll talk on a personal level. All right, I chose to write my first novel as a hobby. It wasn’t an overnight decision because the old rule applied to me: either you have money and no time; or, you have time and no money. Yes, folks, I had to work to pay the bills! There was no time to do what I wanted: to write a historical novel. When I retired from teaching English and translating, I sat down and wrote a 120000-word novel. But then you have to revise it and I’m pleased to say, I reduced it to 90000-words. I still think The Purple Thread is one of my best efforts. I remember telling my wife, “I’ll be happy if only twenty people read it.” After many positive reviews, six years and another nineteen novels to my name, I’m aiming for thousands of readers. Yes, I know, I’d rather it were millions! Still, I love losing myself in my writing, empathising with my characters and travelling in time. I don’t enjoy the hidden aspect, which is marketing and promotion. That is why I found myself a decent indie publisher to help me with it in the shape of Next Chapter Publishing. In my opinion, writing is a lonely occupation, many indie writers, myself included, have a fragile morale. We produce babies (our novels) and want people to love them as much as we do. But, as I suggested earlier, there’s a baby boom out there. The trick is to get your baby noticed. You can enter it in a baby contest and win prizes but so often there’s an entry fee to pay. I’m not mean, but I don’t enter. I may be wrong, but I foolishly think that if my work is good enough, it’ll be appreciated for its worth without stickers. I won’t lie. If I earned (a lot) of money from my writing, I’d be very happy, but it would be a bonus. I do it because I love doing it – as someone said, runners run and writers write. JOHN BENTLEY & THE FRENCH CONNECTION Author, John Bentley is an old friend, we go back to 1972, when we were teaching colleagues in Nottinghamshire. Sadly, we only lived in the same place, Radcliffe-on-Trent, for a short time, but although living miles or countries apart, we always meet up somewhere. On our last meeting in a tea room in Lincoln we had a chat about John’s blossoming writing career. John Broughton: Let’s begin with the most difficult question we all hate answering:

John Bentley: Any answer is liable to sound trite and self-congratulatory, but I’ll try! Throughout my life, I’ve adopted leadership roles: forming musical groups; as a Queen’s Scout from my ranks in the organisation; as editor of my weekly college newspaper; as a head of department on schools; as president of the Nottingham teachers’ union. I think responsibilities such as these have given me the confidence to use the written or spoken word with a degree of success. John Broughton: You have had three novels published. What made you decide to write? John Bentley: If I recall correctly, you had just had your first novel, The Purple Thread published and, during one of my frequent visits to you and Maria in Torano Castello, you challenged me to do the same. Initially, I hesitated, but once I’d said ‘Yes, I will’, I had committed to doing it. I think you also said you’d give me 12 months, by this time next year’, and, give or take a month, I had completed it And they Danced under the Bridge published by Creativia, now Next Chapter. John Broughton: (laughs) You know how I like to give you challenges! Are you a pen and paper writer? Or do you prefer the keyboard? John Bentley: Whenever I answer this question, folk are surprised that I employ what is, to them probably the most time-consuming method possible but, hey, each to his own! My system is as follows: first, given I have the basic idea, I draw a ‘spider diagram’ on an A4 sheet – each ‘leg’ being a thread coming from the ‘body’ in the middle; second, I write down a chapter list showing me the main events and chronology; third, then I start writing Chapter One, but by hand, always with the same black rollerball pen, crossing out and adding as I go along. I estimate that between 12-15 handwritten pages gives me a suitable chapter length although this isn’t set in stone; fourth, it’s then typed onto Word on my pc; fifth I ask my respected mate and novelist, John Broughton, to do a revision of that chapter; finally, I make any amendments needed, on screen, then on to the next… John Broughton: (sniggers) Respected, at last! Where and when do you prefer to write? Do you have a routine? John Bentley: I write in my armchair surrounded by sheets of notes, post-it notes, dictionary and tablet but I type at my desk. A routine? Not really. When I get to a point where further research or thinking is futile, I start typing. But if I get an idea in the night I always get up and jot it down because it will certainly have gone by the morning! Generally, I find the afternoon most productive. John Broughton: Have you ever experienced the dreaded writer’s block? If so, how do you cope with it? John Bentley: Yes, but specifically not knowing which of several starting points to use to get me into a chapter – the first 2 sentences I find painful. I ask myself why? how? when? then just get on with the answers. John Broughton: Well, here we are, enjoying a nice cup of tea; in my case, I drink it even in Italy, but when writing, are you a tea or coffee man? John Bentley: Coffee. John Broughton: (laughing) Now that’s what I call a laconic answer. We’ll leave it at that except to say if anyone’s interested, my answer would be water. Honest! Moving on, when you have an idea for a novel, what’s the spark? A theme? Or a plot? John Bentley: The spark usually comes from looking at a particular period in history, then an event or person in it, then my historical fiction author head takes over the characters and story. John Broughton: Sounds good, but if a reader enjoys one of your books, how does she find out more about you or your novels? John Bentley: I use Facebook a lot but also community sites/forums as well as more national Historical Writers sites. I’m currently reworking my own website. John Broughton: Good luck with that! If you could magically spend a couple of hours with one of your characters, who would you choose to meet up with? Why? John Bentley: The Chain Tower keeper in my third novel, The Guise of the Queen. He’s a wise old sailor who still wears his navy frockcoat with pride. He’s never been asked to perform his duty of stretching the chain across the harbour entrance until now and it’s a great honour. He’d have many tales to tell me. John Broughton: Yes, I’m sure he would! Do you have a favourite author? Can you recommend one of their books? (One you’d willingly read again). John Bentley: Albert Camus, La Peste; Victor Hugo, Les Misérables John Broughton: Ah Monsieur Bentley! The French connection again. I hope people will read your interesting Author biography to understand why. So, what do you enjoy/dislike about writing? John Bentley: dislike: synonyms and metaphors not springing to mind; like: the satisfaction of having a chapter well-written and revised, giving me the impetus to move on to the next. John Broughton: Can you provide one paragraph from any of your novels that best gives an idea of what you’re about as a writer? John Bentley: [Elysium angels looked down on the sad, afflicted, desperate town of Avignon. Saints Jean, Laurent, Martial and the rest had witnessed wise counsel bestowed from the commanding towers of the Palace go unheeded. Patience tested, consumed. This was their day of atonement. Nemesis in her moment, the Furies’ boundless punishment, Hera’s loathing of Zeus: all paled set against the apocalyptic pestilence that had devoured the wicked place. The people with houses not yet shut up stood in line since dawn before the carved stone portal of the Grand Audience. Restless, they awaited the ceremonial opening of its colossal iron-bound doors. In the beginning, the emergency law resulted in congregations increasing tenfold. But the clergy, too, were smitten without mercy and the churches closed, the Audience and the cathedral being the only seats of worship still ministering. Religion played no great part in the citizens’ lives but despair had driven them to clutch at any comfort, to hope against hope, to pray for survival. Old and young, men and women, sound and infirm, babes-in-arms composed the ominous procession. They wore neither festive clothes nor fine sandals. Talk, for what it was worth, was barely audible. They had little to say. The most pernicious event that had or would ever bedevil their lives had rendered them incapable of expressing feelings. Pain in every household, Death personified round every corner, they had become callous, cynical, cold-hearted. They scorned human kindness as a weakness, self-preservation demanded strength not sympathy, but to what end pleasantries? Each knew the lot of the other and the demise of any child ravaged one family as it did a neighbour’s….] (this is the opening paragraph of “And they Danced under the Bridge”, published by Creativia/Next Chapter) John Broughton: Well, I remember reading that paragraph as your beta reader what seems a lifetime ago, and thinking: this is going to be interesting…I wasn’t wrong! Thank you for your time, old friend. If you want to find out more about John Bentley and his historical novels set in France, DOUBLE CLICK on link below: https://davidbentley24.wixsite.com/website

NARRATING THE PURPLE THREAD by MATTHEW SYKESWhen I first got started with The Purple Thread, my primary concern was getting a recording sound that matched with Audible’s specifications. There are certain restrictions around room noise, recording level and several others in technical jargon I still barely understand. A tricky prospect, but after research and building myself a booth in a cupboard surrounded by thick blankets, I was ready. As I read through the book, I was struck by the range of characters and the amount of words I had never seen before. A host of Christian terms as well as the names of people and places from the eighth century. John was a marvellous help, responding to my pleas for assistance with pronunciation tips and feedback.

The quantity of work before was more than a little overwhelming, especially after I had edited the first couple of chapters and realised the amount of time that goes into tidying up audio and pacing the narration. My confidence grew after I had finished a few chapters, with John approving each one, but eleven and a half hours of recorded audio is quite the marathon. Pacing myself became almost as important as recording and reading ahead. I found hours disappearing as I edited, sometimes only removing the smallest little mouth sounds. So, I decided to map the process out, chapter by chapter, giving myself regular breaks and spending more time rerecording rather than endlessly editing small clips of audio unnecessarily. Recording is the best part of narrating an audiobook. It is a time to play around and a time to enjoy the story as well. Finding a good quiet space can be difficult, especially in a city. Planes and trains were a persistent bother, often causing me to have to rerecord long sections. On top of that listening to your own voice takes a while to get used to. Despite that, recording was where I felt the characters come to life and the story breathe. Editing takes patience and time. It took me a while to realise its limits. You cannot fix some things and its important in a project of this scale to not get caught in tiny battles. Still, as the chapters progressed, I felt that the quality of my work did the same and my confidence grew, spurred on by John’s kind encouragement and assistance. I would not want to work on a book without the author’s support, it made the whole project some much better From the first words, Begiloc swiftly became my keystone for this book. I chose a broad west-country accent to mark him out as a man from Dumnonia and became so used to it that it began to slip into conversations. Meryn, his friend, came easily but it took me some time to come up with an idea of how to conjure up the large saxon, Caena. As someone who loves accents, I wanted to try to show the path of the story in the ways that people spoke. We can never know what the Franks, the Lombards or the Saxons sounded like, so I endeavoured to use regional accents of today, careful to stray away from parody. This became particularly difficult with some of the middle eastern accents, and it took me some time to be comfortable with them. As a man, the female characters were also a challenge but again I wanted to avoid caricatures. After listening to my first attempt at Abbess Cuniburg and realising she sounded like something out of Blackadder, I tried softening my voice and raising the pitch a little. After that I found that she, Leoba and Aedre all came more swiftly to life. Some parts of the book took me a little off guard. A rather intimate section, the solemn and harsh attitudes of the powerful figures in the story and a heavy religious emphasis took me some time to get to grips with. Not being a religious man myself, I struggled to put myself in their shoes, feeling sorry for those who were treated badly by those of the church. I found Boniface and Leoba’s fervour uncomfortable at first, and at first, I almost laughed at myself speaking such grand words into my microphone in my little cupboard. With time and more understanding of the characters and the overall story, I found myself settling into their shoes and relishing moments with them. I imagine I would still be working on the Purple Thread audiobook now if I could, wanting every second of it to be perfect. On this side of it, there is plenty I would still like to improve, but I find that is the case for any creative endeavour. I learned a lot throughout the process and working with John was a real pleasure. It was certainly a marathon, but I am proud of it all and I hope you will enjoy listening to it. It’s a great book and I hope that I have managed to do it justice. |

To buy your copy of Rhodri's Furies click the link below:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Rhodris-Furies-Ninth-century-Resistance-incursions-ebook/dp/B0BPX9C2D3/ |